Deferred Price Discovery Under Policy-Supported Valuations

This analysis examines the current South Korean equity market not as a traditional bull cycle or an imminent crisis, but as a system exhibiting deferred price discovery under policy-supported valuation conditions. While headline indices signal stability and success, underlying participation, capital flow, and foreign exchange dynamics reveal a growing divergence between internal price support and external validation. The result is a market that appears stable at the surface level, yet structurally degrades through concentration, delayed adjustment, and rising sensitivity to external constraints—making the timing and form of eventual re-synchronization more consequential than the index level itself.

Deferred Alignment Under Dollar Stress: Korea’s Time-Defense Regime Enters External Price Discovery

U.S. pressure on South Korea is no longer about trade balance or tariff arithmetic. It is about execution under constraint. Howard Lutnick’s January intervention exposed a misalignment between Washington’s reshoring timetable and Seoul’s capacity to absorb external pressure without triggering domestic rupture.

South Korea is not defending its currency; it is defending time. FX intervention, administrative dollar extraction, regulatory concessions, and delayed capital deployment are not independent policies—they are layers of a single time-defense regime designed to survive the June 2026 political threshold. Each layer stabilizes the surface while consuming future optionality.

From an ODP–DFP perspective, Korea’s internal constraints have become legible just as external actors—China through industrial coercion, Japan through alliance anchoring, and the U.S. through enforcement sequencing—begin to price delay rather than rhetoric. Lutnick’s statement reflects urgency, not dominance: the U.S. system is encountering resistance not from defiance, but from constraint saturation.

This is not a crisis state. It is a pre-commitment state, where stability is maintained by postponement, and postponement steadily reallocates epistemic advantage to those with liquidity density, alliance stickiness, and enforcement reach.

Korea’s FX Stress Becomes Administrative: Dollar Repatriation Pressure as Substitute for External Liquidity

South Korea is no longer stabilizing its currency through markets.

It is doing so through power.

When a government sends customs inspectors to 1,138 exporters to force dollar repatriation, it is not enforcing compliance — it is substituting for a missing external backstop. The FX system has crossed a threshold: from technocratic management to administrative extraction.

This is what a high-mass economy does when it runs out of buffers.

Korea is not defending a won level.

It is defending time — until the June 2026 parliamentary election determines whether the current political system survives or fractures.

Behind the façade of stability sit compressed balance-sheet risks: property-finance defaults, household leverage, public absorption of private losses, and a currency kept afloat by reserves, swaps, and now coercion.

The longer adjustment is delayed, the more violent its eventual release becomes.

And as Korea weakens itself to survive politically, it also weakens its position between Washington and Beijing — turning domestic stabilization into geopolitical vulnerability.

This is not a currency story.

It is a sovereignty story.

The U.S. External Balance Regime (2009–2025)

In October 2025, U.S. trade data surprised global markets. The U.S. trade deficit fell to its lowest monthly level since 2009, driven by declining imports and rising exports — yet without triggering recession, financial stress, or domestic contraction. This was not a typical cyclical improvement. It marked a structural transition in how the U.S. economy absorbs external imbalance.

For more than a decade, the U.S. relied on global capital inflows and dollar recycling to finance persistent trade deficits. That regime is now shifting. Under the ODP–DFP framework, the mechanism that once buffered imbalance through financial markets is being replaced by one that manages it through trade flows. Stability remains — but the channel through which it is achieved has changed.

The U.S. external balance is no longer passively financed. It is being actively reconfigured.

South Korea’s FX Reserve Buffer Enters a Managed Depletion Regime

South Korea is not defending a currency level. It is defending time.

Since mid-2025, macro stress has not erupted through sovereign funding, banking instability, or headline inflation. Instead, constraint has surfaced where visibility is lowest: foreign-exchange management and reserve deployment. The system remains operational, but at a growing cost.

Under the current regime, reserves are no longer passive insurance. They have become operational instruments used to smooth volatility, preserve narrative stability, and defer structural adjustment. This substitution strategy sustains surface order while quietly eroding degrees of freedom.

Stability persists. Optionality does not.

What appears as control is, in fact, deferred adjustment — a system absorbing force rather than resolving it. The risk is not collapse, but the moment buffering capacity turns politically salient and time runs out.

Illusory Leadership: BYD’s HKEX Sales Claims and the Structural Failure of Comparable EV Metrics

Global headlines now claim that BYD has overtaken Tesla as the world’s largest electric-vehicle seller. The conclusion is derived almost entirely from a corporate disclosure filed with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange—and then repeated across international media without methodological scrutiny.

This analysis shows why that claim collapses when forced into a system with defined variables. The HKEX filing does not specify what constitutes “sales” or “exports,” nor whether reported volumes correspond to registered vehicles absorbed by end users. In output-driven systems, undefined categories expand easily. In registration-based markets, they do not.

Using the European Union as a falsification benchmark—the largest shared market with auditable vehicle registrations—this report demonstrates that Tesla still leads BYD in real sales. The perceived global leadership is therefore not a market fact, but a statistical projection created by undefined variables under internal pressure.

How BBIU Anticipated Korea’s Structural Deterioration (June–December 2025)

From June 2025 onward, BBIU did not forecast a dramatic collapse in South Korea’s economy.

We forecasted something far more structural — and far more difficult to detect in real time.

While consensus narratives focused on inflation prints, policy rates, and headline growth, BBIU tracked where stress would surface first, who would absorb it, and how the system would preserve surface stability while hollowing out internally.

Household liquidity erosion preceded sovereign stress.

Equity strength functioned as a liquidity exit, not recovery.

FX absorbed pressure before domestic repricing.

Narratives adjusted before policies did.

There was no sudden crisis — only controlled continuity through gradual erosion.

This was not luck.

It was structural sequencing.

Korean Structural Shrinkflation as Policy Regime

When short-term political measures persist beyond their emergency horizon, they cease to be tools and become a governing regime. In open economies, this regime rarely produces immediate collapse. Instead, it generates systemic shrinkflation: the economy continues to function nominally while its productive depth, institutional credibility, and intergenerational solvency are slowly hollowed out.

The cost of stability is displaced. Firms absorb distortion through shortened horizons, regions lose density, and institutional balance sheets—once neutral allocators—are mobilized as shock absorbers. Apparent control persists because deterioration is fractional, asynchronous, and distributed across actors and time.

Argentina demonstrates that an economy can survive decades under repeated emergency interventions without dramatic failure—at the price of eroded complexity, trust, and temporal depth. Korea now faces an early-stage inflection of the same structural pattern: an open, import–export dependent system confronting FX stress and housing fragility while increasingly relying on administrative stabilization and intergenerational capital.

This is not a prediction of collapse. It is a diagnosis of a regime whose defining feature is delayed cost—and whose risk lies not in sudden failure, but in the silent exhaustion of its capacity to absorb.

Balance-Sheet Substitution as Diplomatic Signal

South Korea’s latest FX measures are not designed to solve dollar stress. They are designed to demonstrate restraint.

By exhausting private balance-sheet flexibility before touching official reserves, the state is signaling something more subtle than emergency stabilization: coordination readiness. Banks are mobilized, incentives are recalibrated, and FX smoothing is acknowledged openly—but asset liquidation abroad is deliberately avoided.

Under the ODP–DFP framework, this configuration points to pre-negotiation behavior, not domestic optimization. The system is buying credibility, not resolution. In a politically sensitive global market cycle, Korea’s objective is clear: stabilize FX access without forcing repricing in U.S. asset markets.

This is not an FX defense.

It is a diplomatic signal embedded in balance-sheet substitution.

An Unusual Weekend Signal: Why Korea’s Emergency FX Meeting Marks a Structural Threshold

When South Korea’s foreign-exchange authorities convened an emergency weekend meeting on December 14, the signal was not the won’s exchange-rate level.

It was the room.

The presence of welfare and industry ministries alongside financial and FX authorities marked a quiet but decisive shift: currency stress had crossed from a market-management issue into a systemic constraint on employment, industrial liquidity, and social stability.

This article argues that the recent depreciation of the Korean won is not an external shock but the visible surface of accumulated domestic stress—absorbed first by construction SMEs, project-finance structures, and silent credit rollovers, before being externalized into FX.

Using BBIU’s ODP–DFP framework, the analysis shows why real-asset prices remain rhetorically defended while the currency becomes the system’s primary clearing mechanism—and why this configuration signals not imminent collapse, but the gradual exhaustion of containment capacity.

South Korea’s Liquidity Signal Revisited

South Korea’s current monetary debate is not about whether liquidity exists. It is about what kind of liquidity exists, where it resides, and whether it stabilizes or fragilizes the system under constraint.

The recent confirmation that broad money (M2) has expanded above 8% year-on-year for three consecutive months — reaching ₩4,471.6 trillion — does not invalidate earlier structural warnings. Instead, it exposes the core tension BBIU has consistently identified: aggregate liquidity expansion can coexist with internal liquidity degradation when composition shifts toward market-linked instruments rather than transactional buffers.

The Bank of Korea’s own response — emphasizing investment-fund distortion, FX-driven inflation risk, and the limits of naïve M2 interpretation — signals not resolution, but constraint management. Measurement repair and narrative clarification have become policy tools, indicating that public inference itself is now a stability variable.

This audit finds that BBIU correctly identified the direction of structural stress — FX as the binding constraint, liquidity composition distortion, and stability maintained through interpretive management — while overstating phase certainty in select instances where containment, not terminality, is currently evidenced.

The system is neither collapsing nor unconstrained.

It is becoming legible under pressure.

FED CUTS 0.25%: THE MANUFACTURED STABILITY NARRATIVE IN KOREA VS. THE POLITICAL REALITY IN THE UNITED STATES

Korea’s reaction to the Fed’s 0.25% cut reveals a deeper structural pattern:

when fundamentals deteriorate, narrative replaces analysis.

While international sources describe a fragmented, politically pressured Federal Reserve, Korean outlets transformed a trivial adjustment into a story of stability, inflows, and relief. The gap between what the system is and what the system says about itself is now wide enough to measure.

Behind the mask of stability lie weakening non-semiconductor exports, household leverage at global extremes, industrial relocation to the United States, and FX reserves that are increasingly collateral rather than ammunition. The illusion is maintained not by economic strength but by forced private-sector dollar liquidation and tightly managed media framing ahead of the 2026–2028 political horizon.

The narrative is smooth, reassuring, and coherent —

because the structure underneath is not.

Exporting Collapse: China’s Overproduction System and the Africa Dumping Sink

China’s November export surge is not a signal of renewed global demand — it is the outward projection of an internal collapse.

Behind the headline numbers lies a manufacturing system trapped in chronic overproduction, where unsold EVs and industrial surplus must be pushed abroad to prevent domestic destabilization.

Africa’s sudden import spike is not evidence of rising purchasing power; it is evidence of China’s need to offload excess capacity.

Markets with limited infrastructure, weak regulatory filters, and low retaliatory power become structural dumping sinks in a global realignment driven not by opportunity, but by necessity.

BBIU’s assessment is unambiguous:

China is exporting stress, not strength — and Africa is absorbing the shock.

Korea’s Inflation Mirage: Why Cosmetic Controls Signal the Beginning of Structural Decay

Despite their different geographies, histories, and developmental trajectories, Korea and Argentina are now exhibiting a strikingly similar structural pattern. Both nations—one an advanced industrial power in East Asia, the other a resource-rich South American economy—are drifting toward the same gravitational basin of stagnation.

The mechanisms differ, but the direction is identical.

Korea’s micro-regulatory coercion, moralized inflation narrative, and politically motivated price intervention echo Argentina’s early-stage Kirchnerist playbook:

blame corporations, regulate symptoms, avoid structural reform, distort price signals, and hope that narrative control can substitute for macroeconomic correction.

In both cases, the road begins with small, symbolic interventions—weight-labeling mandates, shrinkflation policing, “consumer protection” rhetoric—but ends in the same systemic destination:

a narrowing policy corridor, declining competitiveness, capital misallocation, and the silent erosion of national talent.

As the two paths converge toward the same chasm—the Stagnation Basin—the warning becomes unmistakable:

countries collapse slowly, not suddenly, and always by following familiar roads already walked by others.

When the State Sells the Private: South Korea’s Forced Dollar Liquidation and the Terminal Liquidity Signal

South Korea has crossed the final boundary of liquidity sovereignty. Following months of silent depletion of domestic deposits and accelerated foreign capital exit, the government has now ordered major conglomerates and the National Pension Service (NPS) to liquidate dollar reserves and inject them back into the domestic system. This transition marks the formal entry into the Terminal Liquidity Phase (TLP): the point at which the state ceases to defend its citizens’ assets and instead begins to harvest them.

Official numbers report foreign reserves at US$428.8B, yet the apparent increase since August mirrors the notional value of the RMB-KRW swap line activated with China — an asset not freely deployable for defending the currency or settling dollar obligations. Adjusted for swap accounting, real usable reserves return to the US$408–412B range, dangerously close to the BBIU-identified insolvency threshold of US$370–380B. The coincidence between household deposit collapse (₩20.2T ≈ US$14.2B) and the reserve bump implies a one-to-one substitution rather than real accumulation: liquidity left the domestic system and was cosmetically replaced with synthetic reserves.

In the historical sequence of financial crises, forced liquidation of institutional FX assets precedes one terminal step: capital controls and deposit seizure. Argentina (2001) followed this exact path. The parallel is now unmistakable: foreign capital has already exited; households are leveraged and exhausted; the state is consuming the last internal liquidity layer. Once corporate treasuries and national pensions are drained, private deposits become the only remaining reservoir.

South Korea is no longer preventing collapse. It is financing time.

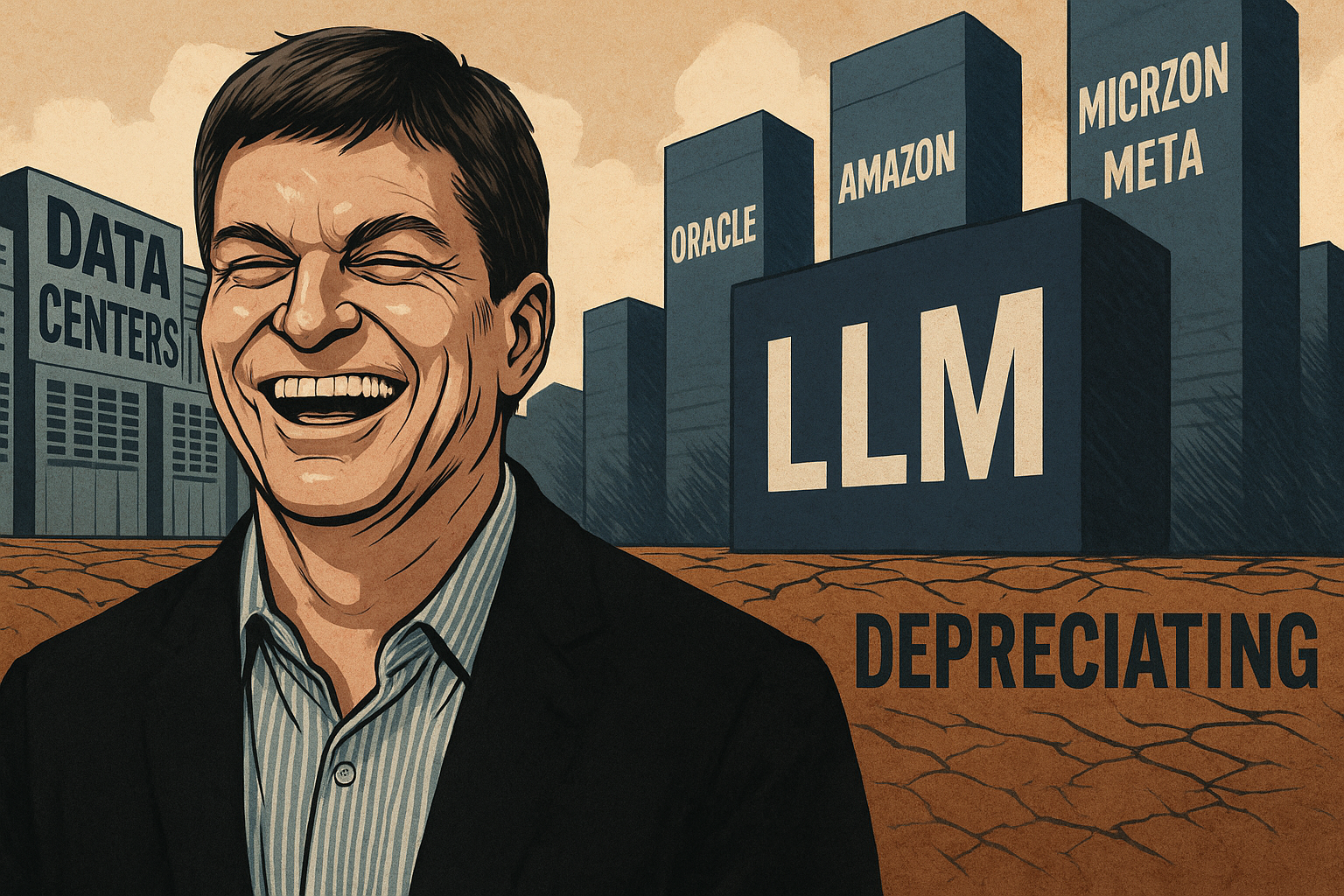

THE FIVE–YEAR AI SUPER-CYCLE AND THE RETURN OF MICHAEL BURRY - How an Unprecedented Technological Boom Met an Old Financial Question

Over the past five years, artificial intelligence shifted from a secondary capability to the central axis of global technology strategy. Hyperscalers such as Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, Amazon, and Oracle committed hundreds of billions of dollars to data centers, AI-optimized chips, power infrastructure, and networking, creating the most capital-intensive build-out the tech sector has ever seen. This expansion depends not only on engineering and demand, but on a quiet accounting assumption: that AI hardware can be depreciated over five to six years, even though its competitive usefulness often declines after two to three.

Michael Burry’s recent intervention targets exactly this gap between physical reality and financial reporting. His thesis is that hyperscalers are overstating the useful life of their AI compute assets, thereby overstating earnings and supporting valuations that assume a slower hardware replacement cycle than the technology actually requires. By taking more than a billion dollars in short positions against key AI beneficiaries, including Nvidia and Palantir, Burry is not betting against the existence of AI, but against the credibility of the earnings profile currently attached to the AI infrastructure boom.

KOSPI 4000 and the Liquidity Paradox: When Speculative Capital Replaces Savings

South Korea’s November stock surge conceals a deeper liquidity fracture. As the KOSPI pierced the 4,000 mark for the first time, investor deposits in brokerage accounts soared to ₩86.8 trillion — a historic high — while bank deposits contracted by ₩21 trillion in a single month. Margin credit climbed to ₩25.5 trillion, reviving leverage levels unseen since 2021.

This second-generation liquidity wave is not investment, but re-leveraging. Households, squeezed by falling sales, high rates, and a weakening won near ₩1,450 per USD, are withdrawing savings to speculate in equities and cover debt through minus accounts. The market’s ascent is financed by desperation, not growth.

BBIU identifies this phase as a Terminal Liquidity Cycle: foreign capital quietly exits while domestic investors absorb inflated valuations. The currency weakens, leverage expands, and solvency erodes — a symbolic inversion where fear becomes price and liquidity replaces productivity as the engine of the economy.

The Forecast Fulfilled: How BBIU Anticipated Korea’s Liquidity Collapse Before the Market Did

In early November 2025, the Korean equity market validated BBIU’s structural forecast with mathematical precision. The KOSPI’s fall from 4,000 to 3,953 and over ₩7 trillion in foreign net selling confirmed that the rally was not driven by institutional strength but by displaced household liquidity. Deposits drained from major banks in late October while brokerage and margin balances surged — a clear sign that savings had been converted into speculative leverage.

BBIU’s October report warned of a liquidity inversion and symbolic misalignment between apparent macro stability and real household stress. That warning materialized within two weeks. The sequence — deposit flight, speculative substitution, foreign exit, correction — unfolded exactly as anticipated. The event demonstrates the predictive capacity of BBIU’s epistemic framework: when leverage replaces savings, price becomes the instrument through which truth returns to the market.

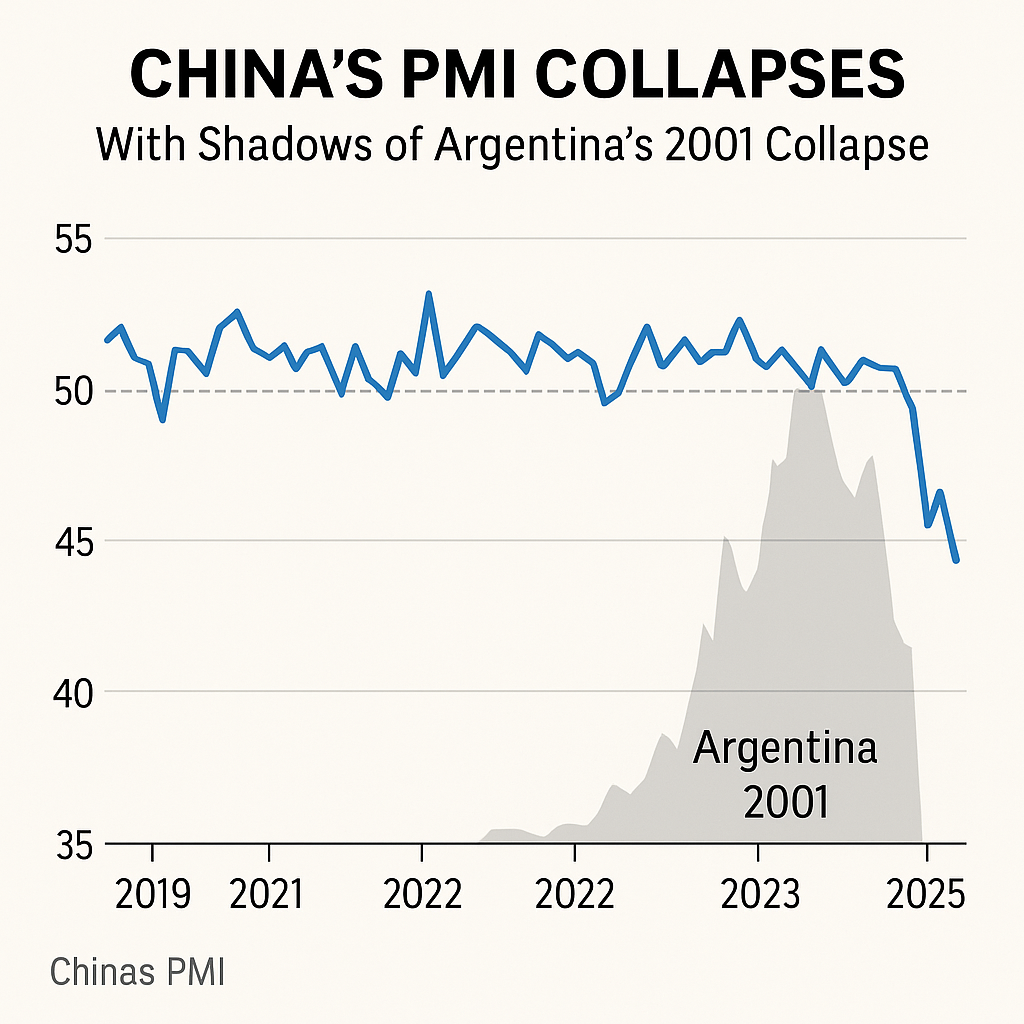

China’s PMI Mirage: Front-Loaded Fear Disguised as Growth

The visual comparison between China’s 2025 PMI and Argentina’s 2001 crisis exposes a shared anatomy of exhaustion hidden behind numerical restraint. In both cases, the index hovered near 49 — a level that to the untrained eye suggests stability but, in structural terms, signals paralysis. Argentina’s PMI plunged from 49 to 39 as the peso–dollar peg imploded; China’s remains suspended near 49 under administrative containment.

The image captures this symmetry: China’s red line declining into opacity, Argentina’s 2001 curve collapsing into blackness. Factories fade into shadow, and beneath them the ghost of Buenos Aires’ bank runs reappears — a reminder that liquidity crises are not only financial but epistemic. The PMI line becomes the common language of denial: one nation lost its currency, the other loses its narrative. Both continued to move after motion had lost meaning.

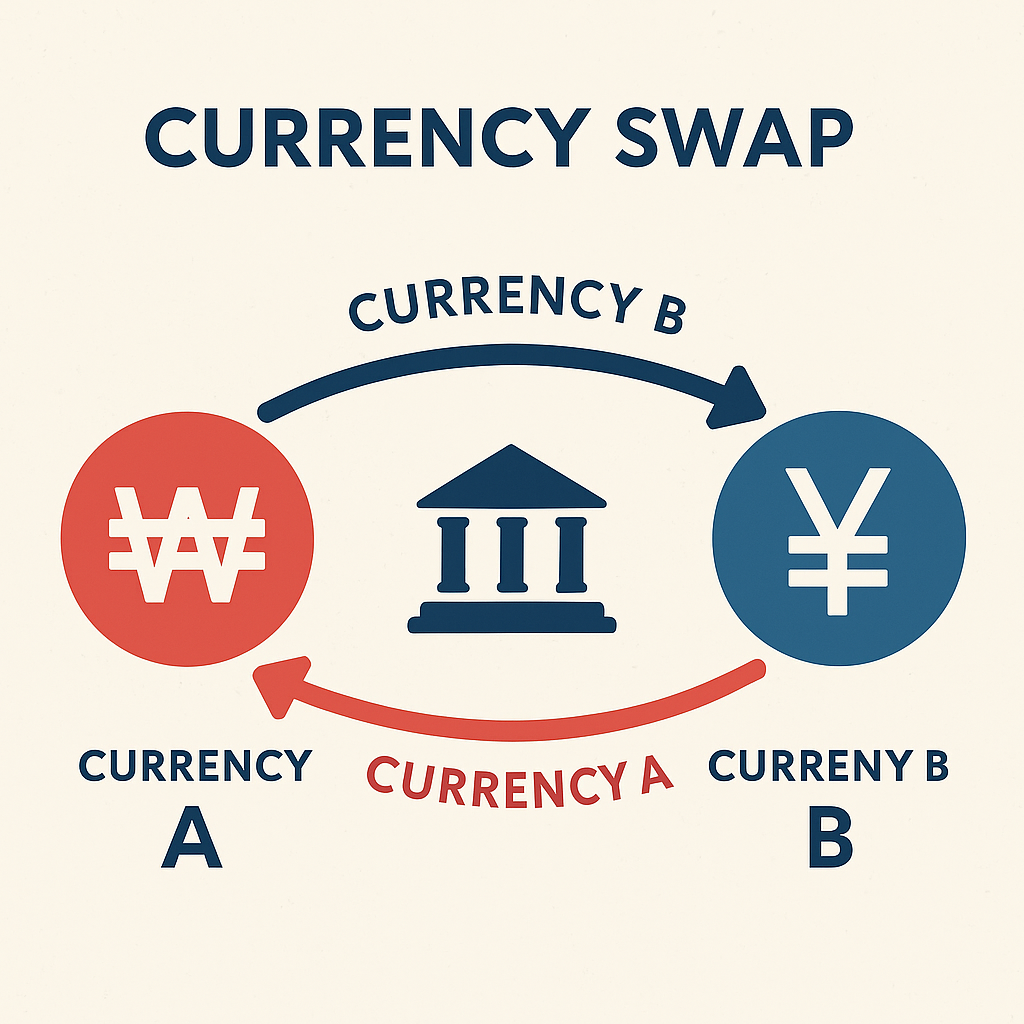

The Won–Yuan Swap: Seoul’s Silent Pivot to Financial Survival

“The Won–Yuan Swap: Monetary Survival Under Geopolitical Compression”

Sources: Reuters, Chosun Ilbo, JoongAng Ilbo, Korea Herald, Bloomberg, ZDNet Korea, People’s Daily

On November 1, 2025, the Bank of Korea and the People’s Bank of China renewed a five-year currency swap worth ₩70 trillion (CNY 400 billion) during the Lee–Xi summit in Gyeongju. Although officially framed as a “new strategic partnership,” the agreement is a reactivation of the expired 2020–2023 facility. Yet its context transforms it from a mere liquidity safeguard into a geoeconomic confession.

Signed less than 48 hours after President Lee gifted Donald Trump a golden crown and golf ball, and just one day after the $350 billion U.S.–Korea deal, the swap signifies strategic suffocation and forced hedging.

It exposes Seoul’s position between two monetary empires: Washington, which withholds access to dollar liquidity, and Beijing, which grants conditional access to yuan circulation.

The arrangement buys optical stability but not autonomy. Activation remains at China’s discretion, and usage will likely be restricted to trade with Chinese entities, echoing the Argentine precedent where yuan swaps became trade-limited lifelines.

What began as financial prudence now functions as oxygen rationing in a dual-sovereignty regime.

Annex I – Currency Swap Mechanics, Risk–Benefit Structure, and the Argentina Precedent

Annex II – Why Korea Needed the Swap: Liquidity, Leverage, and the Anatomy of Structural Suffocation